Reviewed by Rabbi Moshe Maimon and The SeforimChatter Podcast Blog staff

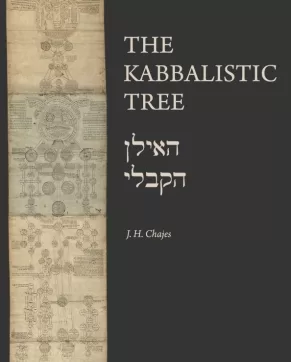

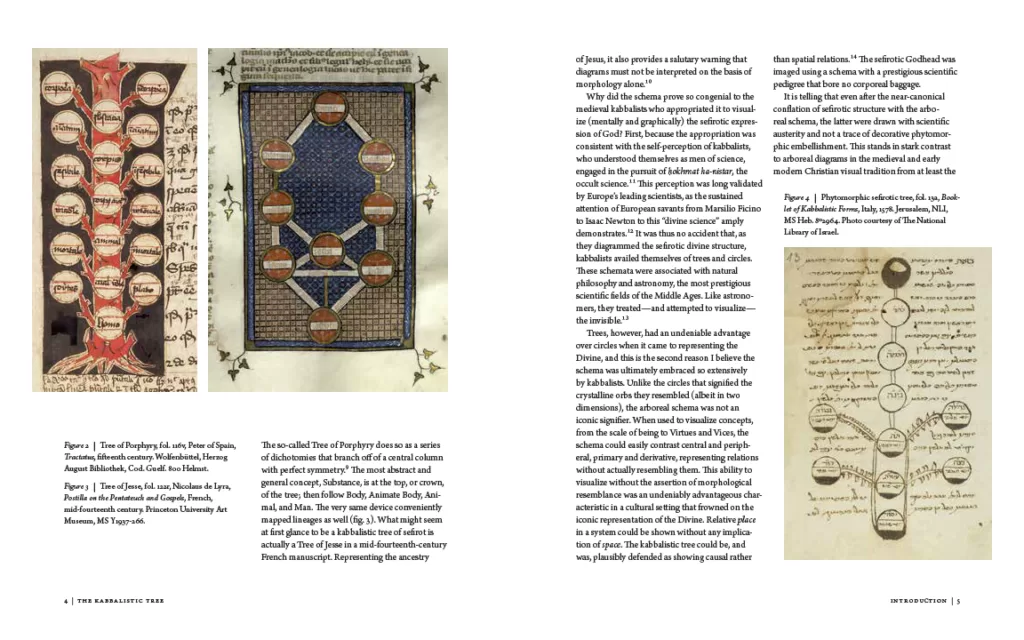

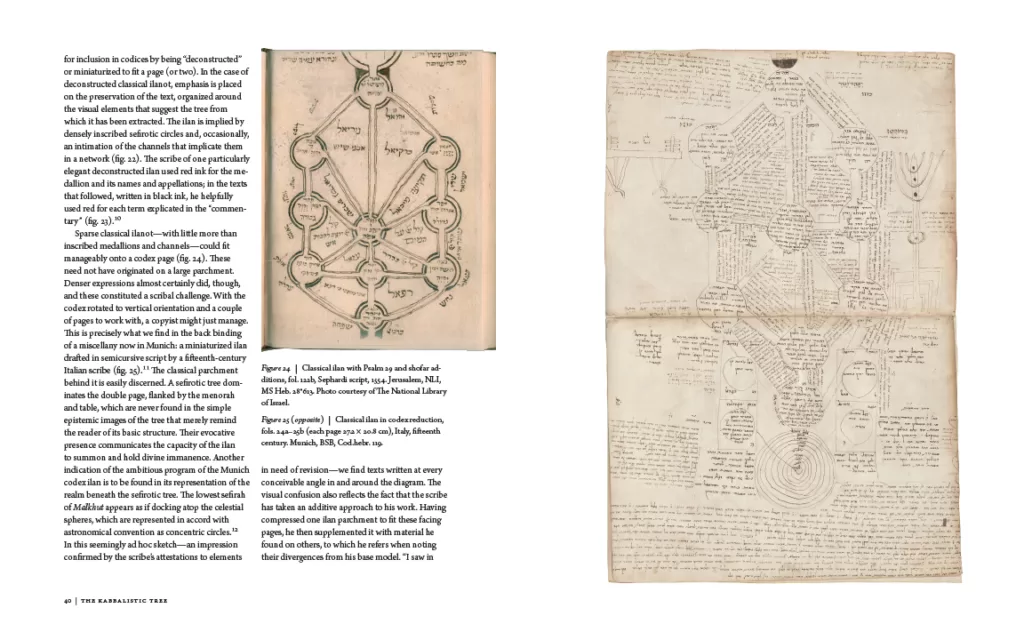

The Kabbalistic Tree is a groundbreaking work that opens to the general public the hitherto unexplored genre of the Ilan, a roll containing diagrams of the intra-divine process, a sort of road map to the kabbalistic universe. The book travels through the various periods in the development of the Ilan: from the classical period in the Middle Ages, with its relatively simple, uncluttered picture of the Ten Sefirot, through the later Lurianic period, when the discovery of the holographic Parzufim (Personae) produced a proliferation of graphics, a virtual explosion.

The author, the Sir Isaac Wolfson Professor of Jewish Thought at the University of Haifa, brings to the table his own extensive background in both theoretical Kabbalah (what he calls the “mathematics” of the Ilan) and art history, and his skill in both fields is on full display as he deftly guides the reader through the labyrinth of exhibits that make up this fantastical museum of kabbalistic history and art.

The volume is particularly rich in high quality color facsimiles of many of the vast array of manuscripts that contributed to this groundbreaking study, and a good number of them are produced to size in full-length foldouts which are of great help in appreciating the fine detail in these manuscript drawings.

Of further bio-bibliographical interest; interspersed in the narrative are biographical sketches of kabbalists who contributed to the development of the Ilan in one way or another. The history of the Ilan is in many ways the history of Kabbalistic development itself, and the thumbnail sketches of kabbalistic greats throughout the centuries adds a lot of color to the reconstruction of this history.

Regrettably, some of these vignettes leave something to be desired. While Chajes went to great lengths to provide the reader with a comprehensive biography of R. Jacob Zemah, a pioneering developer of the Lurianic Ilan, one is left in the dark as to the life and times of Zemah’s disciple, R. Meir Poppers, who provided the next link in the chain. No doubt, Chajes would justify his extensive treatment of R. Zemah on the grounds that seeing him in the context of his converso beginnings in Portugal helps us to understand how that background contributed significantly to the man’s cultivation of the visual arts. Still, at least a glimpse into the world of R. Meir HaKohen Poppers remains a desideratum.

Just the same, readers of this volume will enjoy a unique hands-on tutorial in this yet uncharted field of Jewish intellectual and artistic history, and they will find their knowledge much enriched at the through the able lessons given by the excellent curator of this amazing collection.

The conclusion to this magnificent volume, the “Collector’s Afterword” by William Gross, provides us with the backstory to the so-called Ilanot Project. “In 2005 a serendipitous event occurred.” That serendipitous event (what Kabbalists refer to as “hashgaha peratit”) was the meeting of Dr. Menachem Kallus, an erudite scholar of Kabbalah, and Mr. Gross, a Tel-Aviv collector of antique Judaica. (Many of the Ilanot displayed in the book are from the Gross Fa mily collection.) Eventually, Eliezer Baumgarten, yet another Kabbalah scholar, would join the team. The rest, as they say, is history.

In addition to the book, there is a website (www.ilanot.org) that provides more information on the various Ilanot (including digital critical editions) for those so motivated.

Click here to purchase a copy of the book.

Errata:

p. 289:

“ … [Samuel] Vital lauded Nathan of Gaza as ‘the legitimate heir and representative of the Lurianic tradition.’”192

The endnote on page 397, note 192 references Scholem, Sabbatai Sevi, p. 276. But Scholem there is referring to Samuel Vital, not to Nathan of Gaza! Samuel Vital “was certainly entitled to be regarded as the legitimate heir and representative of the Lurianic tradition.”

p. 385, end note 55:

Teplitsky, Prince of the Press, 30

30=50

One Response

On the Ilanot Website, they note that you an use discount code ILANOT to buy the Kabbalistic Tree from Penn State for $59.99 instead of $99.99